Edit your Blog articles from the Pages tab by clicking the edit button.

Read MoreBorn on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas, she was raised in a family that encouraged curiosity and independence. From an early age, Earhart defied traditional gender roles, climbing trees, collecting insects, and showing a fascination for adventure.

Her first encounter with aviation came in 1920, when a brief airplane ride ignited a lifelong passion for flying. Just three years later, she became one of the first women in the United States to earn a pilot’s license.

Determined to prove that women could excel in aviation, she set numerous records, including in 1932 when she became the first woman—and only the second person after Charles Lindbergh—to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic Ocean.

She went on to establish new speed and distance records, publish books about her experiences, and champion opportunities for women in aviation and beyond. In 1937, Earhart set out with navigator Fred Noonan on her most ambitious journey yet: a flight around the world along the equatorial route.

After covering more than 22,000 miles, their plane vanished on July 2 near Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean.

Despite massive search efforts by the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard, no trace of the plane or its crew was ever found. Her disappearance remains one of history’s greatest unsolved mysteries.

Amelia's Early Childhood...

Amelia's Early Childhood (ages 0 to 9)...

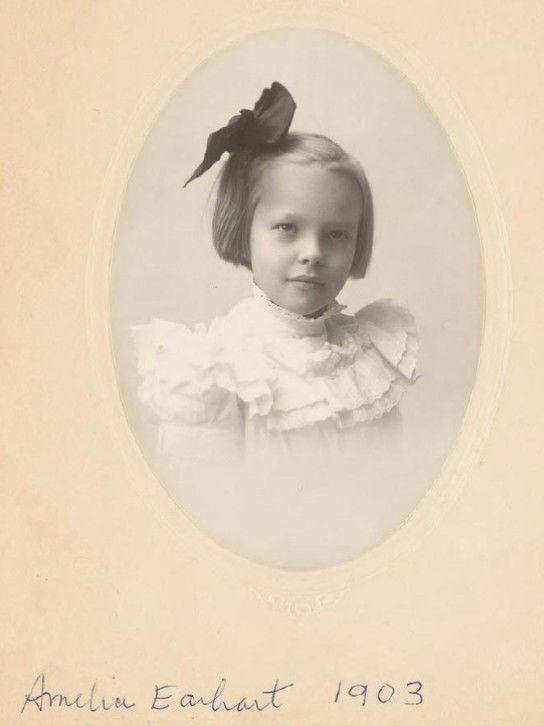

Amelia Mary Earhart was born on July 24, 1897, in Atchison, Kansas, in the home of her maternal grandfather, Alfred Gideon Otis—a former judge, president of the Atchison Savings Bank, and one of the town’s most prominent citizens.

She was the second child of Samuel "Edwin" Stanton Earhart and Amelia "Amy" Otis Earhart, and she came from a family of mixed heritage, including German ancestry. Amelia’s namesake came from both of her grandmothers—Amelia Josephine Harres and Mary Wells Patton—in keeping with family tradition.

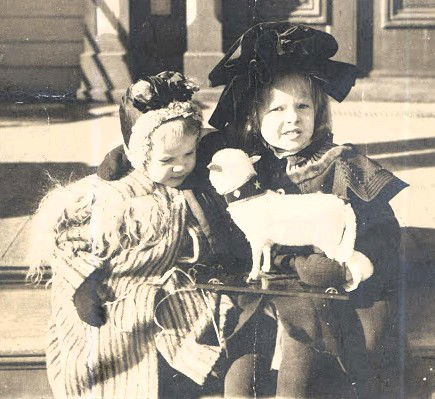

From an early age, Amelia stood out as strong-willed and independent. She often took the lead over her younger sister, Grace Muriel Earhart (affectionately called "Pidge"), who was born in 1899 and tended to be more compliant.

The Earhart children seemed to have a spirit of adventure and would set off daily to explore their neighbourhood. As a child, Amelia Earhart spent hours playing with sister Pidge, climbing trees, hunting rats with a rifle, and sledding downhill. Some biographers have characterized the young Amelia as a tomboy and they use to keep worms, moths, katydids and a tree toad.

In Atchison, Amelia enjoyed a relatively stable and nurturing environment. Her grandmother, in particular, instilled values of education and proper behavior, while Amelia’s natural curiosity often pushed against such constraints. By age 3 or 4, she was already demonstrating independence and a keen sense of adventure, qualities that would become trademarks throughout her life.

At just seven years old, inspired by a roller-coaster she saw at the 1904 St. Louis World's Fair, she and her sister Muriel built a homemade “roller coaster” on top of their tool shed using boards, a box, and a tub of lard—Amelia rode the contraption down, crash-landing but emerging exhilarated, and Amelia proclaimed the wild ride felt “just like flying” afterwards (This episode captures both her daring and her imagination: qualities that foreshadowed her aviation career decades later).

Amelia herself was nicknamed “Meeley” or “Millie”, and both sisters kept these nicknames well into adulthood. The Earhart household was anything but conventional. Amy Earhart believed in giving her daughters the freedom to explore and develop their own interests, rather than conforming to traditional expectations of “proper young ladies.”

At this age, Amelia had not yet entered a traditional school system consistently; her education was piecemeal and often guided by her mother and grandmother. Her curiosity, however, was evident: she devoured books and enjoyed creating imaginary worlds during play.

While their maternal grandmother disapproved of the bloomers the girls wore, Amelia enjoyed the sense of freedom they gave her—even if she was aware that other neighborhood girls were dressed more traditionally.

Summary Table (Ages 0–9)

Age Range | Key Events & Experiences |

|---|---|

0–6 | Lived mostly with grandparents in Atchison; stable early environment; encouraged in education and manners |

6–8 | Developed tomboy spirit; loved climbing, hunting, sledding; famous homemade roller coaster incident at age 7 |

8–9 | Continued adventurous play; early exposure to instability from father’s alcoholism; informal education guided by family |

Amelia Earhart’s Formative Years (Ages 10–19)

Amelia's Ten to Teen Years...

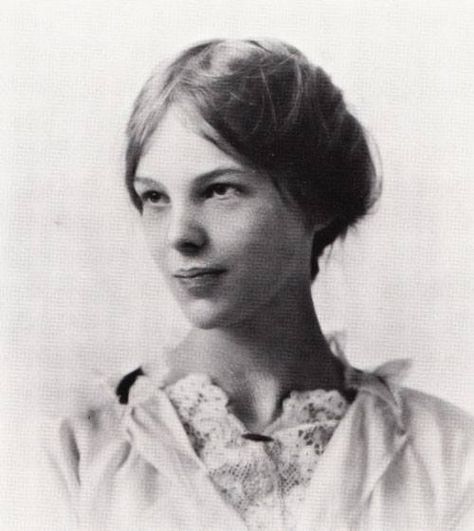

Between ages 10 and 19, Amelia Earhart’s character was forged through upheaval, independence, and curiosity. She endured family instability, navigated social isolation, and rejected conventional expectations for women of her time.

Her scientific curiosity, admiration for pioneering women, and exposure to both the tragedy of war and the marvel of flight laid the foundation for her groundbreaking aviation career in the decade that followed.

Early Adolescence (Ages 10–13)

By the time Amelia was about 10 years old, her father got a job with the Rock Island railroad and the family moved to. Des Moines, Iowa.

It was here that Amelia first entered public school for the first time as a seventh grader (Wikipedia).

Around this time she witnessed her first airplane at the 1908 Iowa State Fair. Surprisingly, the sight of the “thing of rusty wire and wood” failed to inspire her—she later admitted it seemed uninteresting and primitive (Amelia Earhart official biography). At the time, the merry-go-round was far more appealing than the idea of flight.

Her adolescence was marked by instability. Her father, Edwin Earhart, battled alcoholism, and his erratic employment forced the family into repeated relocations.

The death of Amelia’s grandmother in 1911 also removed one of her most stable anchors.

Mid-Teens and Shifting Identities (Ages 14–16)

In 1913, Edwin got a job in St. Paul, Minnesota and the family relocated here. In the spring of 1914, Edwin took another job in Springfield, Missouri, but after moving, discovered that the man he was to replace had decided not to retire.

As her father’s difficulties worsened, Amelia’s mother separated from him, taking Amelia and her sister Muriel to live independently.

Rather than return to Kansas with Edwin, where he eventually started his own law practice, Amy took her children to live with friends in Chicago’s tony Hyde Park neighborhood. Amelia’s shame and humiliation over her father’s alcoholism and from watching her mother struggle financially caused a lifelong dislike for alcohol and need for financial security.

The family eventually settled in Chicago in 1915. There, Amelia carefully researched local high schools and deliberately chose Hyde Park High School, which she believed offered the strongest science curriculum (Biography.com).

Her independence was already apparent. In the 1916 Hyde Park High yearbook, she was described as “A.E.—the girl in brown who walks alone” (Wikipedia). Despite social isolation, Amelia excelled academically, particularly in science, and cultivated her sense of individuality.

At this stage, she also began keeping a scrapbook filled with newspaper clippings about successful women in law, engineering, film direction, and management—an early sign of her determination to challenge gender conventions (Amelia Earhart official biography).

She graduated high school in 1916, a significant milestone given her family’s frequent upheavals.

Late Teens and First Steps Toward Ambition (Ages 17–19)

Earhart graduated from Hyde Park School in 1915 and the following year enrolled at the Ogontz School in Pennsylvania, an elite finishing school for young women. Her ultimate goal was to attend Bryn Mawr, then Vassar.

Over the Christmas break during her second year, in 1917, she visited her sister Muriel, in Toronto, Canada, where she was attending St. Margaret’s College. It was here that Amelia encountered many World War I veterans and, although she was already helping with the war effort at Ogontz as secretary of the Red Cross chapter, she wanted to do more.

She soon realized the prescribed path of domesticity and social refinement did not suit her ambitions.

She and Muriel spent time at a local airfield watching the Royal Flying Corps train. Choosing to contribute, she left Ogontz to volunteer as a nurse at Spadina Military Hospital and during 1918 trained as a nurse’s aide at the hospital. (Notable Biographies, Wikipedia). Many of her patients at this hospital where many of her patients were French and English pilots.

This experience exposed her to hardship and resilience, deepening her commitment to meaningful, adventurous work. During this period, she also attended a flying exhibition in Toronto, which reignited her imagination about aviation—a passion that would soon define her life.

Timeline...Summary Table (Ages 10–19)

Age Range | Key Events & Experiences |

|---|---|

10–13 | Moved frequently; first saw an airplane at Iowa State Fair; unimpressed; grandmother’s death brought instability |

14–16 | Family settled in Chicago; Hyde Park High School (strong science focus); socially isolated but independent; collected clippings of pioneering women; graduated 1916 |

17–19 | Attended Ogontz finishing school briefly; moved to Toronto; volunteered as a nurse’s aide during WWI; inspired by flying exhibitions; early seeds of aviation passion planted |

The Soaring Journey: Amelia Earhart – Twenties to 1937

A Young Woman Drawn to the Skies

In the early 1920s, aviation was still in its infancy, and female pilots were virtually unheard of. Earhart, in her early twenties, lived in a world where social expectations for women were tightly constrained.

Early Twenties: Awakening to Flight

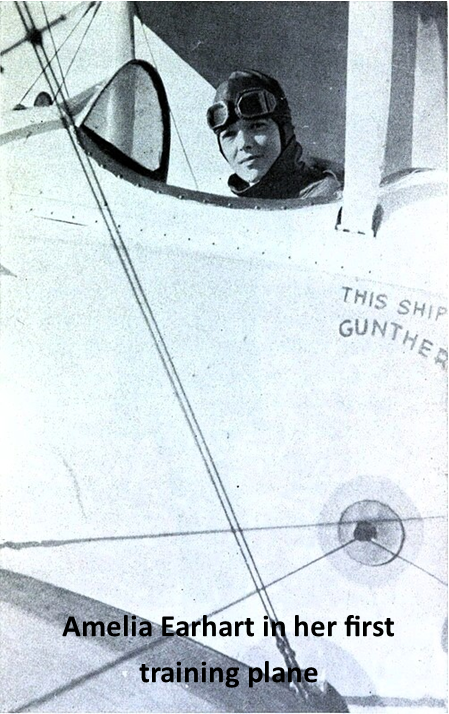

Amelia Earhart’s journey in aviation began with a transformative 10-minute plane ride with veteran pilot Frank Hawksin in December 1920 at an air show in Long Beach, California. She later reflected, “By the time I had got two or three hundred feet off the ground, I knew I had to fly.” (Live Science).

Within months, she had saved money for lessons with Neta Snook, one of the few female flight instructors in the U.S. Within six months, she purchased her first aircraft—a bright yellow biplane (she lovingly called The Canary) , with it, she broke the women’s altitude record in 1922, climbing to 14,000 feet. This was an era when aircraft were fragile machines of wood and fabric, so her achievement captured attention both in aviation circles and among women’s rights advocates.

Mid-Twenties: First Recognitions and Records

Earhart earned her pilot license in May 1923, becoming the 16th woman licensed by the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale (Live Science).

Late Twenties (1928): Atlantic Fame

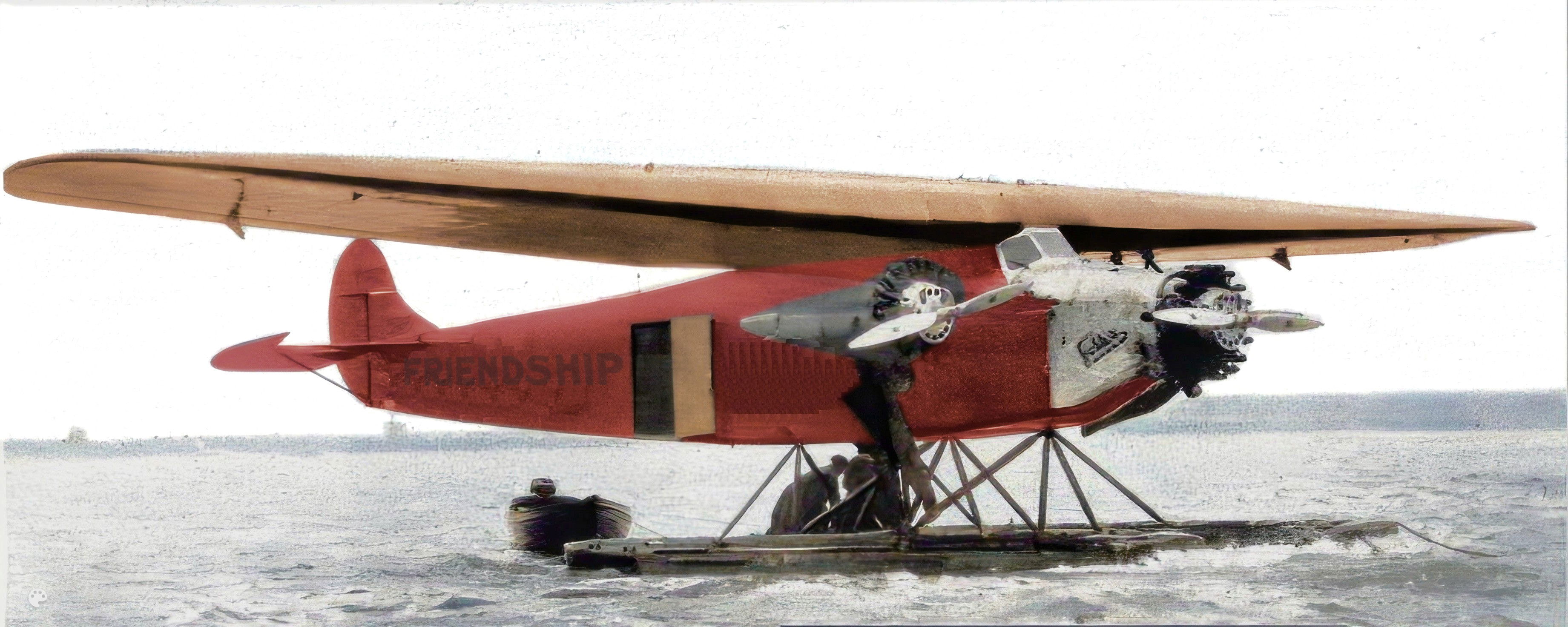

In 1928, at age 30, Earhart journeyed aboard the Friendship as a passenger on the first transatlantic flight by a woman. Though she didn’t pilot the aircraft, the feat turned her into a global celebrity. Reporters compared her to Charles Lindbergh, dubbing her “Lady Lindy,” a nickname that stayed with her throughout her career. She received a ticker-tape parade in New York and was showered with media attention.

The publicity was overwhelming—parades, receptions at the White House, and a book deal quickly followed. Earhart understood the cultural significance of her visibility: she could inspire women by showing what was possible beyond traditional roles. During this period, she became a sought-after speaker and columnist, using her platform to advocate for women in aviation and other professional fields.

Early Thirties: The “Lady Lindy” Era

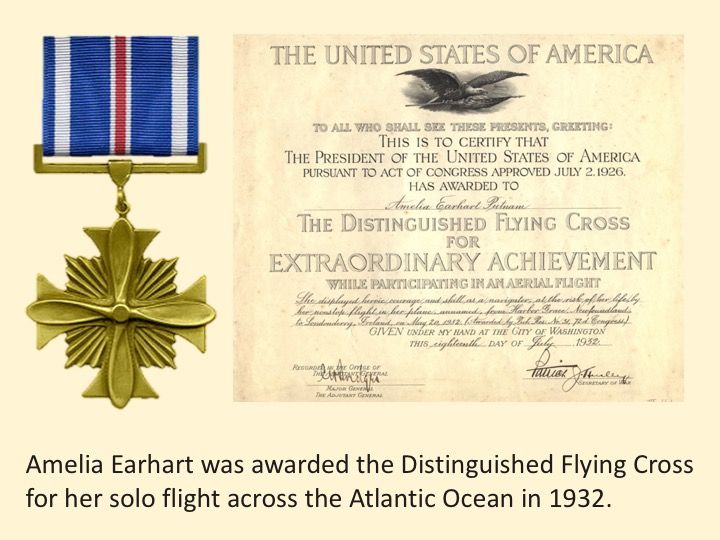

Solo Transatlantic Flight (1932): On May 20, she became the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the Atlantic, battling icy weather, mechanical problems, and exhaustion, she landed in a field in Northern Ireland after 15 hours—a feat that mirrored Charles Lindbergh’s journey exactly five years earlier. This daring achievement made her the first woman, and only the second person after Lindbergh, to do so. She was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross—the first woman to receive the honor.

Continental U.S. and Pacific Records: Her momentum didn’t stop there. In August of the same year, she became the first woman to fly solo nonstop across the continental U.S from Los Angeles to Newark. By 1935, she became the first person to fly solo from Hawaii to California—a particularly dangerous route over open ocean. These records not only demonstrated technical skill but also helped normalize the idea of women undertaking dangerous, high-stakes endeavors.

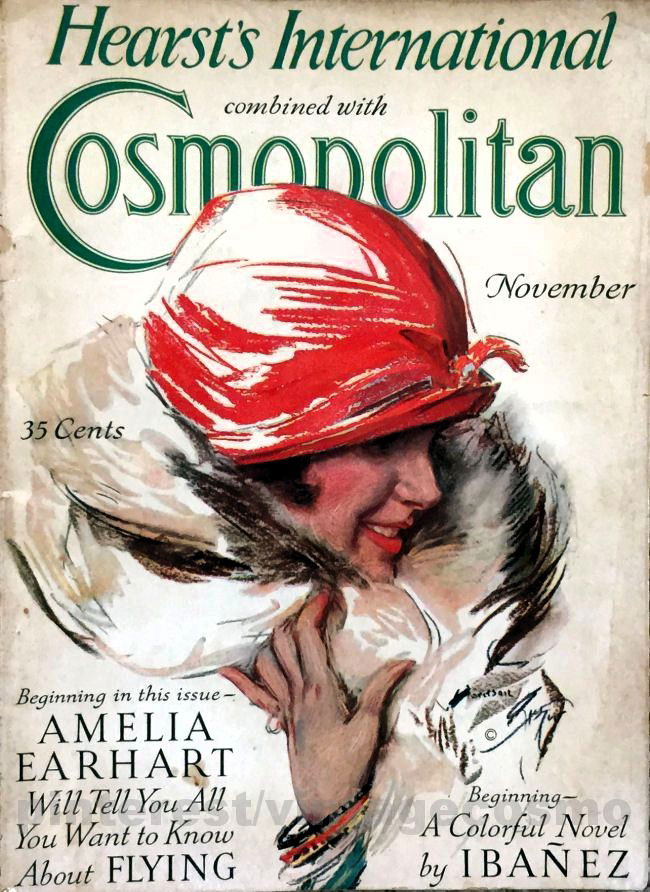

Alongside her flights, Earhart was also a prolific writer and speaker. During this period, she also became aviation editor for Cosmopolitan (1928–1930) where she encouraged young women to pursue bold careers and published two books: 20 Hrs. 40 Min. (1928) and The Fun of It (1932), the latter encouraging women to break societal norms.

Personal Choices and Partnerships

Earhart’s personal life reflected her progressive spirit. In February 1931, Earhart married publisher George Palmer Putnam (after reportedly six proposals) who went on to play a crucial role in shaping her public image. Yet she insisted on maintaining independence in her marriage, famously writing a letter to Putnam stating that she would not be bound by conventional expectations.

She remained committed to her career, even writing to him that she “shall not hold you to any mediaeval code of faithfulness”—placing aviation above conventional expectations. Their partnership was built as much on professional collaboration as personal companionship—Putnam helped organize her flights and public appearances, while Earhart focused on her passion for flying and women’s advancement.

Mid-Thirties: Preparing the World Flight

By 1935, Earhart was appointed a consultant in careers for women at Purdue University. Appointed as a visiting faculty member, she served as a career counselor for female students, encouraging them to dream beyond traditional boundaries. Purdue also helped finance her Lockheed Electra, the aircraft she would use in her final, ill-fated flight which she referred to as her “flying laboratory.”

The Fateful Final Flight (1937)

By the mid-1930s, Earhart wanted to attempt her most ambitious project yet: a flight around the world. While others had circumnavigated the globe, none had done so at the equator, which would be the longest possible route. This venture was not just about personal ambition—it was also framed as a scientific expedition, with her aircraft outfitted as a “flying laboratory” for research and navigation experiments.

Westbound Attempt and Ground-Loop Incident

Her first attempt in March 1937 ended in disaster when her Electra was damaged in a ground-loop accident in Honolulu. After repairs, she and her navigator, Fred Noonan, tried again in June, this time flying eastward. They successfully crossed South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, arriving in Lae, New Guinea, with only the Pacific stretch left.

Eastbound Departure and Progress

Resuming their plan, they began again on June 1, flying eastbound from Miami. Over several weeks, they refueled across South America, Africa, India, and Southeast Asia, reaching Lae, New Guinea by June 29—at this point, 22,000 miles of their 29,000-mile journey had been completed.

Disappearance Near Howland Island

On July 2, Earhart and Noonan departed from Lae, heading to Howland Island—just 2,500–2,600 miles away. A U.S. Coast Guard cutter, the Itasca, waited offshore to assist, but poor radio contact and challenging navigation hindered help. Earhart’s transmission that they were "running north and south" along a navigational line was their last message.

Search and Loss

The plane is believed to have crashed roughly 100 miles from Howland Island, and the search—then the most extensive and costly in U.S. history—ceased after weeks with no trace found. Earhart and Noonan were declared lost at sea; Earhart was legally presumed dead on January 5, 1939.

Theories and Legacy

The Official “Crash-and-Sink”

Government investigators and most historians conclude Earhart ran out of fuel and crashed into the Pacific near Howland Island—a scenario supported by radio logs and search efforts.

Nikumaroro Castaway Hypothesis

TIGHAR proposes that Earhart and Noonan, missing Howland, may have landed on Nikumaroro (then Gardner Island). Artifacts—including shoes, Plexiglas fragments, and bones—found by expeditions support the theory, although no conclusive proof exists.

Other Speculations and Recent Efforts

Alternate theories—such as capture by Japanese forces—persist despite lack of evidence. Technological efforts continue: a recent sonar image captured by a private exploration near Howland has reignited interest, though experts caution that confirmation remains elusive.

Summary Table: Era Highlights

Period | Highlights |

|---|---|

| Early 1920s | First flights, altitude record, pilot license (1922–1923) |

Late 1920s (1928) | First female transatlantic flight as passenger; celebrity status |

Early–Mid 1930s | Solo records, writings, aviation advocate, publications, marriage |

1937 Final Voyage | Ground-loop crash; resumed eastbound world flight; disappearance June–July |

Post-Disappearance | Multiple theories; searches continue, enduring legacy |

Achievements and Inspiration

Few names in aviation history are as instantly recognizable as Amelia Earhart. More than a pilot, she was a pioneer, record-breaker, author, and advocate who inspired generations to dream beyond limitations. At a time when women were discouraged from pursuing daring ambitions,

Read MoreAmelia Earhart inspired far more than just aviation. She also became a symbol of courage, independence, and pushing boundaries, which spilled into culture, education, literature, and social progress. This is a timeline of non-aviation–oriented things inspired by Amelia Earhart.

Read MoreWidely celebrated for her aviation feats, but her leap into fashion, though brief, was bold and prescient and by incorporating practicality with everyday wear, she not only financed her flying but helped reshape the language of women’s clothing, paving the runway for modern functional fashion.

Read MoreThe Ninety-Nines, Amelia Earhart’s visionary “club,” has evolved into a cornerstone of women's aviation—a legacy of empowerment, resilience, and flight. This article celebrates not just a historical moment, but an ongoing journey that continues to inspire aviators everywhere.

Read MoreBurry Port: - Historical background

A History of Burry Port, South Wales

Burry Port is a coastal town in Carmarthenshire, situated on the northern shores of Carmarthen Bay, approximately five miles west of Llanelli.

It occupies a strategic position at the mouth of the Loughor estuary, where the land gives way to wide tidal sands and marshes. Today the town is widely recognised for its harbour, sandy beaches, and strong sense of community life, but its origins as a settlement are relatively recent.

The town as it is known today owes its existence to the industrial expansion of South Wales during the 19th century. Before that period, the area was sparsely populated farmland on the edge of the parish of Pembrey.

The rapid growth of coal mining in the Gwendraeth Valley, coupled with the demand for new facilities to export coal and metals, brought about the construction of Burry Port Harbour in the early 1830s. This development transformed the coastline and gave rise to a new settlement that quickly grew into a thriving town. The history of Burry Port is closely bound to coal and copper, two industries that shaped the entire region of South Wales during the Victorian era.

Its harbour became a gateway through which the products of the Carmarthenshire coalfield reached markets across Britain and overseas. Shipping dominated daily life, with docks, warehouses, and railway links forming the backbone of the town’s economy.

Yet Burry Port’s past is not only industrial. In 1928, the town became the unlikely focus of world attention when the American aviator Amelia Earhart landed there following her pioneering transatlantic flight. This singular event added an international dimension to Burry Port’s history, ensuring that its name would forever be associated with both industry and aviation achievement.

Burry Port Docks Area circa 1928

Early Settlement

Before the harbour was constructed, the landscape where Burry Port now stands was very different from the busy town it later became. The area consisted largely of open farmland, salt marshes, and tidal flats along the Burry estuary. The low-lying land was shaped by the rhythms of the tide and was better suited to grazing animals than to large-scale arable farming.

Smallholdings and scattered cottages dotted the landscape, but there was no organised settlement resembling a town. The nearby village of Pembrey was the traditional centre of local life for many centuries. Pembrey has medieval origins, with its parish church of St Illtyd dating back to at least the 12th century, and documentary evidence pointing to an established agricultural community during the Norman period. Its position slightly inland offered more secure ground than the marshy coastal plain, making it the natural hub of the surrounding district.

Local people in the pre-industrial era relied on farming, fishing, cockling, and small-scale rural industries such as weaving and lime burning. Coastal resources were important too; the broad sands of Carmarthen Bay provided fishing grounds and shellfish, while the estuary and creeks were used for small boats trading in coal, timber, and limestone on a local scale.

Despite this activity, Burry Port as a distinct settlement did not exist until the 19th century. It was the industrial revolution, particularly the demand for coal exports, that transformed the coastline and created the conditions for the new town to emerge. The building of a purpose-built harbour in the 1830s marked the beginning of Burry Port’s development as a separate community, distinct from its older neighbour Pembrey.

Industrial Growth and the Harbour

The transformation of Burry Port gathered pace in the early 19th century, driven by the rapid expansion of the South Wales coalfield. Coal was the foundation of the region’s industrial power, fuelling ironworks, copper smelting, and steamships, while also becoming one of Britain’s most important exports.

The Gwendraeth Valley, just inland from the Carmarthenshire coast, was rich in coal seams, but without an efficient means of transport, much of its potential remained untapped.

The opening of Burry Port Harbour in 1832 provided the vital solution. The harbour was specifically designed to handle large volumes of coal shipments, equipped with quays, basins, and storage areas to accommodate the growing demands of trade. Tramroads and later railway lines were constructed to connect the harbour directly with the collieries of the Gwendraeth Valley, ensuring that coal could be transported swiftly from pithead to ship.

The harbour became the nucleus of a thriving town. Around it, new warehouses were built for storing coal and other goods, while shipyards emerged to construct and maintain vessels.

The arrival of the Llanelly and Mynydd Mawr Railway in the mid-19th century further boosted the town’s connections, linking it not only to the coalfields but also to nearby industrial centres such as Llanelli and Swansea.

This made Burry Port an important link in the chain of South Wales’ export network. Industrial growth also transformed the social fabric of the area. Workers and their families arrived in increasing numbers, drawn by employment opportunities in the docks, railways, and associated industries. Rows of terraced houses, nonconformist chapels, schools, and shops appeared, turning what had once been open marshland into a bustling urban community.

By the latter half of the 19th century, Burry Port had established itself as a significant industrial hub. Its economy was heavily dependent on the export of coal, but other trades, including copper processing, ironworking, and general shipping, also flourished. The town’s position on Carmarthen Bay gave it both local importance and international reach, firmly cementing its role in the wider industrial history of South Wales.

The Copper and Coal Era

While coal remained the backbone of Burry Port’s prosperity, the town was also closely connected to the copper industry, which shaped much of South Wales in the 18th and 19th centuries.

The region between Swansea and Llanelli became known as “Copperopolis”, a global centre of copper smelting, thanks to its access to coal, water, and good harbour facilities. Burry Port, situated between these two larger industrial centres, inevitably became part of this network.

Coal from the Gwendraeth Valley was exported in large quantities through Burry Port Harbour, but the port also handled imports of raw materials such as copper ore. Much of this ore arrived from as far afield as Cornwall, North Wales, and South America, feeding the smelting works that were established along the South Wales coast.

Although Burry Port itself never rivalled Swansea in scale, its harbour supported smaller local copper operations and provided vital shipping capacity to relieve pressure on neighbouring ports. By the mid-19th century, Burry Port’s dual role in coal and copper cemented its status as a busy industrial hub. Railways converged on the docks, wagons of coal trundled down from the valleys, and vessels of all sizes sailed in and out of the harbour.

In addition to copper, other trades developed, including iron, tinplate, and limestone, all of which relied on the harbour for transport. The town developed a strong working-class identity, shaped by coal miners, dockworkers, and their families. By the latter half of the century, Burry Port was firmly established as part of the wider industrial landscape of South Wales.

Its economy was tied to the rise and fall of coal and copper, and its harbour remained the centrepiece of local life. Though it could not rival the scale of Swansea or Llanelli, Burry Port played a significant supporting role in the region’s industrial success, ensuring its place in the history of the Carmarthenshire coast.

Building the Harbour

The driving force behind Burry Port’s growth was the urgent need to find new and efficient outlets for the coal mined in the Gwendraeth Valley and surrounding coalfields.

By the early 19th century, South Wales had become one of the most important coal-producing regions in the world. Llanelli Harbour had already been developed to serve this booming trade, but it soon became congested, and its tidal limitations made it difficult to accommodate the growing volume of shipping. Merchants, industrialists, and landowners sought alternative facilities that could ease the bottleneck and expand opportunities for export.

The result was the construction of Burry Port Harbour, a major undertaking intended to serve as a rival to Llanelli.

Work on the harbour began in the late 1820s, and in 1832 the docks were officially opened. The new harbour featured stone-built dock walls, tidal basins, and lock gates designed to manage the movement of ships in and out of the estuary. Its location on the northern edge of Carmarthen Bay gave it access to deep water and made it well suited to large vessels carrying coal, iron, and other cargoes.

The harbour was not an isolated project; it was part of a wider transport network that included railways and canals. Early tramroads connected the harbour with the collieries inland, and in the following decades these were upgraded into proper railway lines, allowing coal to be transported quickly and in large quantities.

This integration of rail and maritime trade gave Burry Port a competitive edge, drawing business away from neighbouring ports.

The creation of the harbour also brought about the creation of a new town. As workers and their families arrived to service the docks, operate the railways, and work in associated industries, houses, shops, chapels, and schools appeared around the harbour. What had been open marshland and scattered farmsteads was rapidly transformed into a planned urban settlement. Significantly, the name of the harbour "Burry Port" was soon adopted by the town itself, firmly linking its identity with the docks that gave it life.

Industry and Expansion

The mid-19th century saw rapid industrial growth. Burry Port became a focal point for the export of coal and iron, while copper smelting also became established in the area, in line with the wider development of South Wales as “Copperopolis.”The arrival of the Llanelly and Mynydd Mawr Railway (later connected to the Great Western Railway) in 1852 integrated Burry Port further into regional trade networks.

Workers and their families settled around the harbour, and the town expanded with new streets, chapels, schools, and shops. By the late 1800s, Burry Port was a thriving industrial settlement, its harbour bustled with ships carrying coal and metals to markets across Britain and beyond.

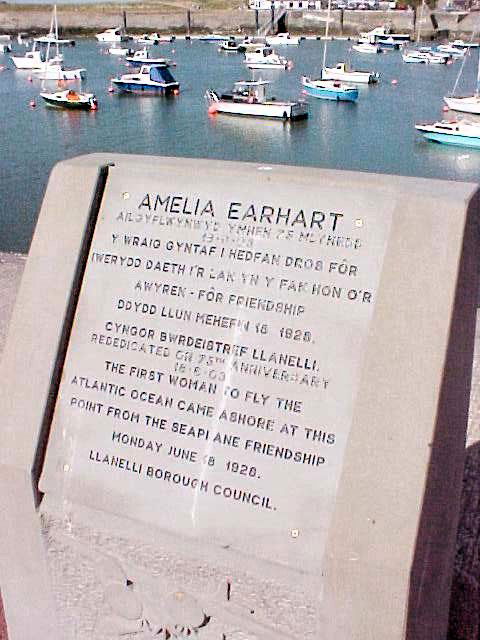

Amelia Earhart’s Landing, 1928

One of the most famous events in the town’s history occurred in June 1928, when American aviator Amelia Earhart became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air. She was a passenger on the seaplane Friendship, which made landfall in Burry Port Harbour after a flight from Newfoundland.

Though Earhart did not pilot the plane herself, the achievement brought her international recognition and secured Burry Port a place in the annals of aviation history.

Today, a plaque near the harbour commemorates the landing.

Decline of Industry and Modern Development

Like many industrial towns in South Wales, Burry Port’s fortunes were tied to the coal industry, and when that industry began to contract, the effects were deeply felt.

From the early 20th century onwards, the global demand for Welsh coal declined as oil and other energy sources became more widely used. International markets that once relied on Carmarthenshire coal began to dwindle, and the docks at Burry Port saw fewer ships entering their basins. The decline accelerated after the Second World War, when many of the surrounding collieries closed permanently.

Without coal exports to sustain it, Burry Port Harbour fell gradually into disuse. By the mid-20th century, the bustling industrial activity that had defined the town for over a hundred years had largely disappeared. Warehouses stood empty, the railway sidings fell quiet, and the shipyards that once serviced vessels lay idle. This industrial downturn brought significant social and economic challenges.

Families who had depended on coal mining, smelting, or dock work often faced hardship, and younger generations sought opportunities elsewhere. The decline of heavy industry left a physical as well as an economic mark on the town, with spoil tips, disused pits, and redundant harbour infrastructure standing as reminders of a vanished era.

Yet Burry Port, like many Welsh communities, adapted and gradually reshaped itself in the post-industrial period. By the late 20th century, the harbour had been redeveloped for leisure use, becoming a marina for fishing boats, yachts, and pleasure craft. Instead of coal wagons, the docks now welcomed visitors seeking to enjoy the scenic coastline.

The construction of the Millennium Coastal Path in the 1990s and early 2000s further transformed the area, creating a landscaped route for walkers and cyclists along the Carmarthenshire coast. Burry Port Harbour became a focal point of this regeneration, serving as both a reminder of the town’s industrial heritage and a centre for recreation and tourism.

Today, Burry Port stands as a town that has moved beyond its industrial origins while retaining pride in its history. Its harbour, once a symbol of coal and copper, is now a symbol of renewal, linking the town’s industrial past to its modern role as a coastal community with natural beauty and a distinctive heritage.

Burry Port Today

In the present day, Burry Port is best known not for its coal exports or shipbuilding, but for its harbour, beaches, and welcoming community.

The shift from an industrial town to a coastal settlement centred on leisure and tourism has redefined its character, while its history continues to shape local identity. The harbour, once crowded with colliers and cargo vessels, now functions as a marina for fishing boats, yachts, and sailing craft. It serves as a hub for recreational activities, drawing visitors from across South Wales and beyond.

The nearby sandy beaches stretch along Carmarthen Bay, offering safe bathing and panoramic views across to the Gower Peninsula and the Loughor estuary. Burry Port also benefits from its position on the Millennium Coastal Path, a 13-mile route linking Llanelli with Pembrey and beyond. This path has become one of the town’s major assets, encouraging walking, cycling, and eco-tourism while reconnecting the community with its waterfront.

The surrounding area includes the popular Pembrey Country Park, with its woodlands, dunes, and the expansive Cefn Sidan beach, further enhancing Burry Port’s appeal as a destination. Despite the changes of the last century, the town has retained much of its heritage character. Historic chapels, Victorian terraces, and the surviving dock walls of the harbour all stand as reminders of its industrial past.

Community groups and local historians have worked to preserve and share this heritage, ensuring that the story of coal, copper, and Amelia Earhart’s landing remains central to the town’s identity. Modern Burry Port is a resilient and vibrant community, shaped by its history yet looking to the future. Its economy now rests on small businesses, tourism, and services rather than heavy industry, but the pride of its people in their town remains unchanged.

For visitors, it offers both a window into the industrial past of South Wales and the chance to enjoy one of the most attractive stretches of coastline in Carmarthenshire.

Burry Port and Amelia

June 18th, 1928 – A Day to Remember in Burry Port...

In the summer of 1928, the world was still caught up in the thrill of aviation’s golden age. Flight was no longer a novelty, but a bold new frontier where each record shattered opened the door to possibilities once thought impossible.

The skies had become a proving ground for courage and ingenuity, and every successful crossing or daring stunt seemed to capture headlines as symbols of human progress. Only a year earlier, Charles Lindbergh had stunned the world with his groundbreaking solo flight across the Atlantic in the Spirit of St. Louis.

His 33-hour journey from New York to Paris not only secured his place in history but also transformed aviation from an experimental pursuit into a symbol of modernity and global connection. Following his achievement, the public imagination was gripped by the idea that airplanes could unite continents, shorten distances, and make the impossible routine.

Aviation in the 1920s was still fraught with risk. Aircraft were fragile compared to modern machines, dependent on good weather, skilled pilots, and sheer determination. Engines could fail, navigation was rudimentary, and survival on a transatlantic crossing was far from guaranteed. Yet these dangers only heightened the allure. Pilots were celebrated as heroes, and their machines as marvels of technology pushing the limits of human endurance.

It was against this backdrop of excitement and uncertainty that a small coastal town in Wales, far removed from the glamour of Paris or New York, became the stage for the next chapter in aviation history.

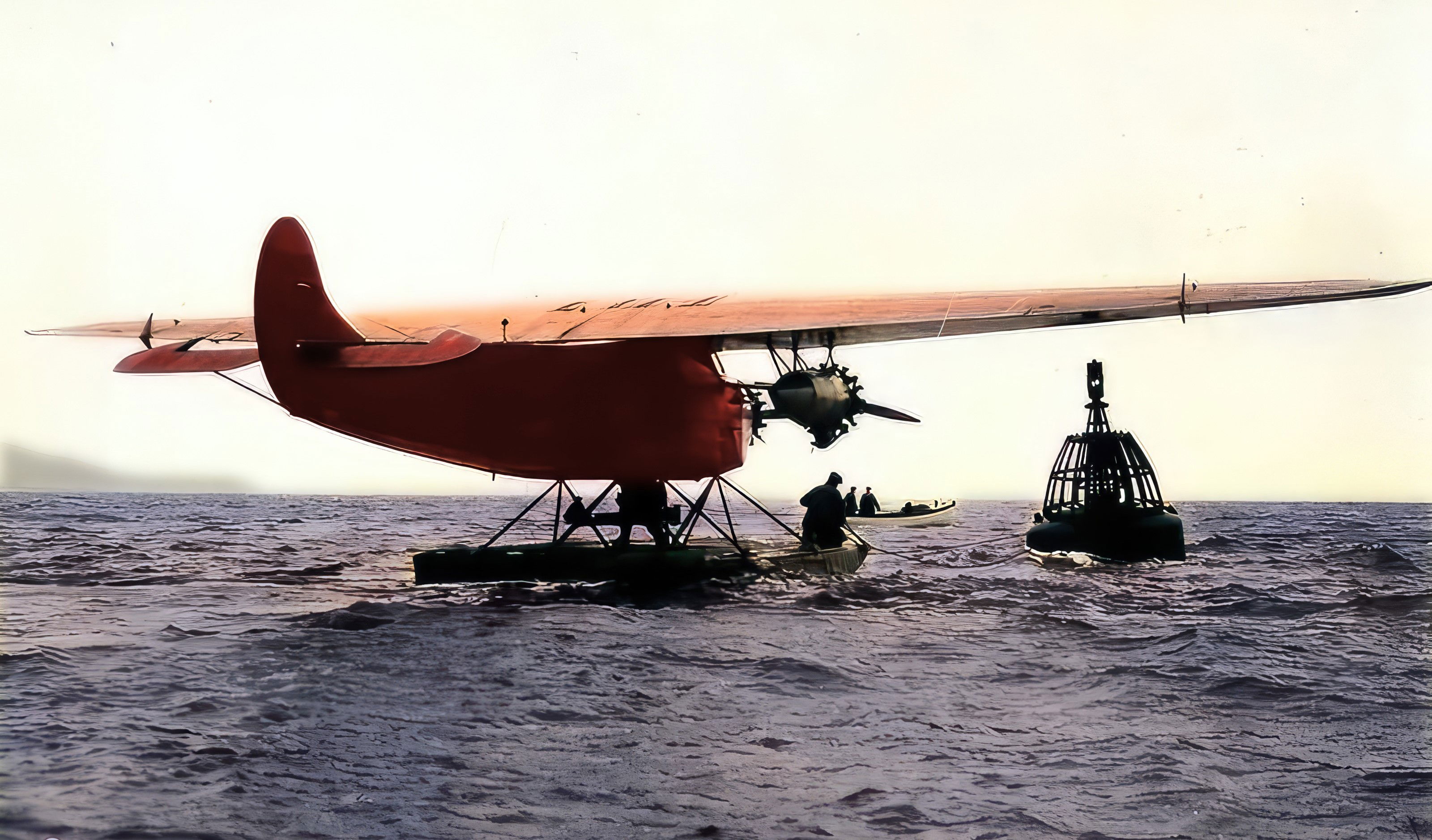

On June 18th, 1928, Burry Port’s tranquil harbor and sandy shores welcomed the Friendship, a bright orange monoplane carrying Amelia Earhart and her crew. For the people of the town, it was an astonishing interruption to daily life; for the world, it was the continuation of aviation’s relentless march forward, proof that the Atlantic, once a formidable barrier, was quickly becoming a bridge.

The Crossing of the Friendship

On June 17th, 1928, anticipation hung heavy in the air at Trepassey Harbor, Newfoundland. It was from this quiet fishing outpost that the "Friendship", a bright orange Fokker F.VIIb/3m monoplane, prepared to make its daring leap across the Atlantic. Painted in vivid orange to maximize visibility should disaster strike at sea, the aircraft was a sturdy trimotor design, built for endurance rather than speed.

At the controls sat "Wilmer Stultz", a skilled American pilot with a reputation for precision and calm under pressure. Alongside him was "Louis Gordon", the dependable mechanic and co-pilot, who would be responsible for keeping the aircraft’s three Wright Whirlwind engines running smoothly through the long, uncertain night.

Their passenger, however, was the one destined to capture the world’s attention, "Amelia Earhart". At just 30 years old, Earhart was already unusual among women of her time. A social worker by profession and a licensed pilot by passion, she had logged hours in the cockpit at a time when female aviators were still a rarity.

To the sponsors of the flight, she was chosen as much for her quiet determination and resemblance to "Charles Lindbergh" as for her flying skill. To Amelia herself, this was not just an adventure, it was the chance to prove that women could take part in aviation’s boldest challenges. The "Friendship" lifted off into the skies that afternoon, its engines straining against the weight of fuel tanks filled for the daunting journey ahead.

What followed was more than 20 hours of tense endurance. The crew faced banks of thick fog that obscured their path, sudden squalls that battered the wings, and the mental fatigue of navigating over an ocean with few reliable instruments. Stultz bore the burden of piloting, with Gordon keeping constant watch on the engines, while Earhart, bundled against the cold, documented the journey and provided steady companionship through the long hours.

By the time the first faint outline of the Welsh coastline emerged from the mist on June 18th, relief and exhaustion coursed through the crew. Yet the flight was not over, they still had to find a safe landing site before their dwindling fuel forced them down. Spotting the broad, flat sands near the harbor town of Burry Port in Carmarthenshire, Stultz guided the Friendship down through the clouds and onto the beach.

For the townspeople, it was an unforgettable sight: a great orange bird descending from the sky, its engines rumbling, settling onto the sands as children and fishermen rushed to see what had arrived. For the crew, it was the end of a perilous crossing, and for Amelia Earhart, it was the moment when an ordinary woman stepped firmly into the pages of history.

Earhart’s Role and Its Meaning

Although Amelia Earhart did not pilot the Friendship herself, her crossing marked a watershed moment: she became the first woman ever to traverse the Atlantic by air. In an era when aviation was still perilous and largely male-dominated, her presence on board was not only a personal triumph but also a symbolic breakthrough.

The 1920s had already witnessed profound social change, women in Britain and America had secured the right to vote earlier in the decade, more women were entering higher education and the workforce, and traditional expectations of femininity were being questioned. Against this backdrop, Earhart’s transatlantic crossing resonated as part of a wider movement toward equality and empowerment.

The press wasted no time in turning her into an international icon. Journalists quickly dubbed her the “Lady Lindy,” a reference to "Charles Lindbergh", whose 1927 solo flight across the Atlantic had captivated the world.

The comparison was deliberate, Amelia’s slim build and short haircut invited parallels with the famous aviator, but more importantly, it positioned her as his female counterpart, a pioneer who could carry the banner of aviation into new territory for women. Newspapers across America and Europe celebrated her as a trailblazer, her name suddenly known far beyond the circles of aviation enthusiasts. Yet the achievement was not without its complexities.

For all the public adoration, Earhart herself felt a twinge of discomfort. She later confessed that she had felt like “a sack of potatoes” during the flight, a passenger rather than a pilot, carried across the ocean rather than actively conquering it. Her honesty revealed both her humility and her ambition. She understood that while the world might see her as a heroine, she had not yet proved to herself, or to her critics that she could match her male counterparts in skill and daring.

Nonetheless, the Friendship flight changed everything for Earhart. Overnight, she became a household name, invited to ticker-tape parades, receptions, and lectures. She secured book deals and speaking engagements, which she used not only to tell her story but also to advocate for women in aviation.

The crossing gave her a platform – one that she would not waste.

Just four years later, in 1932, she silenced any doubts by completing her own solo transatlantic flight, piloting from Newfoundland to Ireland in just under 15 hours. This time there could be no question: Amelia Earhart had matched Lindbergh’s feat on her own terms, becoming the first woman, and only the second person ever, to fly solo across the Atlantic.

What began with the "Friendship" landing in Burry Port as a symbolic step had evolved into a personal and historical triumph. Earhart had transformed from a passenger into a pioneer, cementing her legacy not only as an aviator but as a cultural icon whose courage still inspires today.

The Town That Welcomed History

For the people of Burry Port, the arrival of the Friendship was nothing short of astonishing. The late afternoon calm was broken by the steady drone of engines overhead , a sound still rare in 1928, especially in a quiet harbor town.

Children playing along the shore were the first to notice the strange aircraft circling low, and soon the whole community gathered to see what was happening. Instead of settling onto the sands, the bright orange trimotor descended gracefully onto the waters of the Loughor estuary, just off the harbor.

It was an extraordinary sight: an aircraft built for endurance floating on the tide in a small Welsh port, having just conquered the Atlantic. For many onlookers, it was the first time they had seen a plane up close, let alone one that had come all the way from North America.

Once the crew, pilot Wilmer Stultz, mechanic Louis Gordon, and their passenger, Amelia Earhart, were ferried ashore, they were greeted by an eager crowd. Though weary from more than 20 hours in the cramped, freezing cabin of the Friendship, they were welcomed with warmth and curiosity. Locals brought tea, bread, and simple meals, turning what might have been a mere technical stop into a moment of human connection.

Word of the landing spread quickly, drawing journalists and photographers to Burry Port. Within days, reports appeared in newspapers across Britain, Europe, and the United States. The small town found itself catapulted into the global spotlight, its name forever linked to the age of flight and to Amelia Earhart’s rise as a pioneer of aviation.

For Burry Port, the landing was more than a fleeting spectacle, it was a brush with world history. The quiet Welsh harbor had become, for one remarkable day, the stage on which the future of aviation was written.

History had landed, quite literally, on our shores.

Legacy Beyond the Landing

Earhart would go on to inspire millions with her courage, determination, and unwavering independence. The 1928 crossing of the Atlantic marked only the beginning of a remarkable career. In the years that followed, she set speed and altitude records, became the first woman to fly solo across the Atlantic in 1932, and continued to push the limits of what was thought possible for women in aviation.

Her adventurous spirit and refusal to conform to expectations made her a global icon, embodying the optimism and boldness of an era that was still learning how to dream with wings.

For Burry Port, the landing of the Friendship became its own kind of legend. What had been an ordinary fishing and harbor town suddenly found itself mentioned in newspapers from London to New York. Locals proudly recounted the day when an orange monoplane touched down in their estuary, carrying a woman who would become one of the most celebrated aviators in history. For decades, the memory of June 18th, 1928 was passed down through families and community storytelling, an event that gave the town an enduring connection to global history.

Today, nearly a century later, Burry Port continues to embrace that heritage.

A memorial and plaque stand near the harbor, quietly marking the place where Amelia Earhart’s journey ended and the town’s story entered the history books. Visitors can still walk the same shoreline where crowds once gathered in astonishment and imagine the sound of engines breaking the quiet skies. There is also a monument just opposite the Memorial Gardens in the Town of Burry Port.

It is a reminder that history is not always written in great capitals or grand cities.

Sometimes, the most extraordinary chapters unfold in small, unexpected places. On that June afternoon in 1928, Burry Port became more than a coastal community, it became the finish line of a pioneering transatlantic flight and a symbol of how even the most unassuming towns can find themselves at the heart of world events.

Overnight in Pembrey

How Long Did Amelia Earhart Stay in Burry Port—and Where Did She Stay?

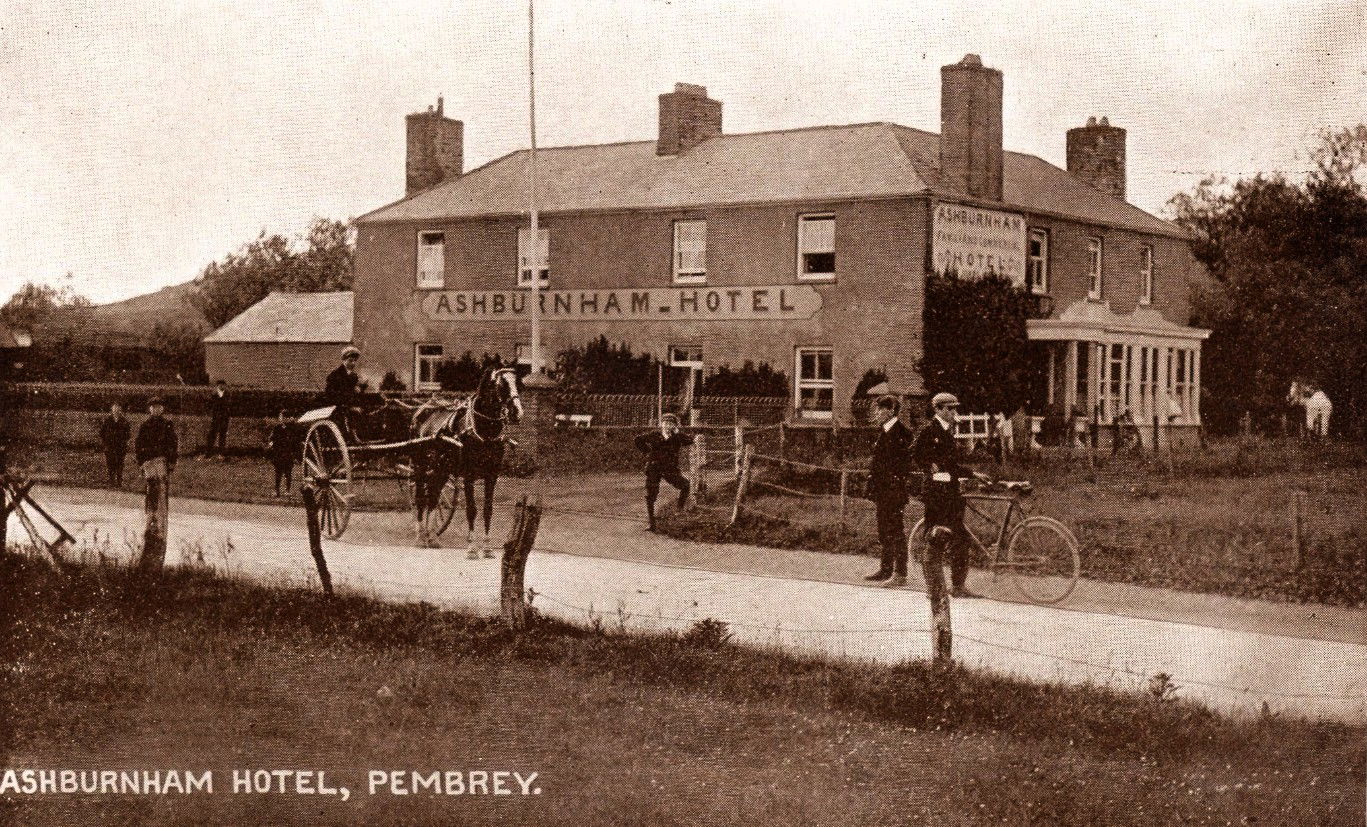

Overnight Stay at the Ashburnham Hotel

Amelia Earhart and her crew landed on the Loughor Estuary near Burry Port around 12:40 pm on 18 June 1928, after their transatlantic flight aboard the seaplane "Friendship". Weather and tidal conditions prevented an immediate onward journey, so they spent the night at the nearby Ashburnham Hotel in Pembrey. They resumed their journey the next morning, 19 June 1928 at around 11 am, departing from Burry Port Harbour to continue toward Southampton.

Accommodation & Historic Remarks

The Ashburnham Hotel, with a rich lineage as a 19th-century coaching inn, holds the distinction of hosting Earhart’s historic overnight stay. Today, guests can stay in the "Amelia Room", named in her honour, a fitting tribute to her pioneering achievement .

That evening, surrounded by reporters and local attention, Earhart shared a poignant reflection with Alice Jones, the hotel’s proprietor at that time: -

“How lovely your country is... The stillness and the silence brings back again the almost awesome feeling… To think that 48 hours ago I was in America and now I am in Wales!”

Early photo of the Ashburnham Hotel

The Amelia Room at The Ashburnham Hotel

Operated today as a welcoming coastal landmark steeped in heritage, The Ashburnham Hotel prominently celebrates its aviation milestone. As detailed on its official site, the hotel highlights its role in hosting Earhart and her crew, and offers guests the chance to stay in the "Amelia Room"—a subtle yet meaningful homage that connects guests to her legacy while enjoying a warm and historical setting.

Recent renovation plans further aim to refresh the hotel’s interiors while preserving its authenticity and historical charm—ensuring the Amelia connection remains at the heart of its character.

To find out more about this lovely, historical hotel follow the link....

The Ashburnham Hotel – The Ash Bar & Grill

A Near-Miss with Aviation History

The following morning, a dramatic moment unfolded; Sir Arthur Whitten Brown, famous alongside John Alcock for the first nonstop transatlantic flight in 1919, had traveled from nearby Swansea to congratulate Earhart. Alas, a boat dispatched to him arrived too late, the "Friendship" had already departed, missing a poignant meeting between two aviation trailblazers

Summary Table

Aspect | Details |

|---|---|

Newspaper Coverage | Early quotes emphasized Wales’ beauty and serenity; local lore enriched over time. |

Anniversary Commemoration | 75th anniversary festival in 2003 featured plaque and reflected community pride. |

Artistic Tributes | Works by Ruth Lewis created from community inspiration, exhibited nationally. |

Current Heritage Marker | The Ashburnham Hotel’s "Amelia Room" serves as a living tribute to her stay. |

Commemorative Acknowledgement

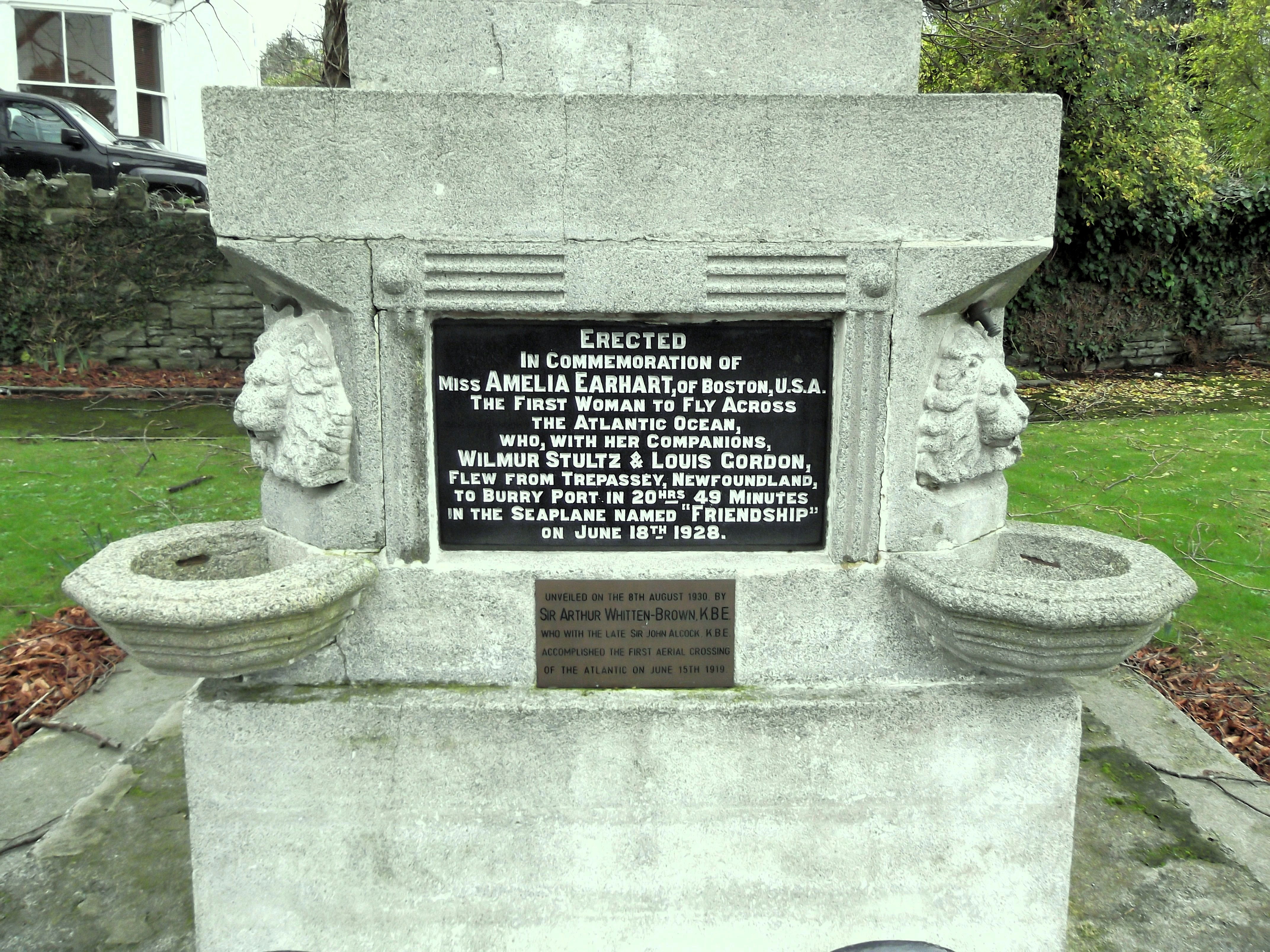

Amelia Earhart Monument

Origins and Significance

The monument was erected in 1930 to commemorate the historic landing of the seaplane "Friendship"—piloted by Wilmer Stultz, with Amelia Earhart aboard, on the Loughor Estuary near Burry Port on 18 June 1928. Earhart thereby became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air.

It stands as a tribute to her pioneering spirit and the local moment that thrust Burry Port briefly onto the global stage.

Design and Unveiling

Designed as an "obelisk memorial", the structure is made of reconstituted stone and stands approximately 20 feet tall. It is positioned on a square base with a stepped plinth. Each corner of the base features corbelled basins beneath lion-head fountains, integrating both form and function.

The monument is adorned with a metal weathervane on top, shaped like the Friendship seaplane—a fitting and visually striking tribute.

Inscriptions on the main plaque read: -

“Erected in commemoration of Miss Amelia Earhart, of Boston, U.S.A., the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, who, with her companions, Wilmer Stultz & Louis Gordon, flew from Trepassey, Newfoundland, to Burry Port in 20 hours 49 minutes in the seaplane ‘Friendship’ on 18th June 1928.”

A secondary plaque notes: -

“Unveiled on the 8th August 1930, by Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown, K.B.E., who, with the late Sir John Alcock, K.B.E., accomplished the first aerial crossing of the Atlantic on June 15th 1919.”

The monument was officially unveiled on 8 August 1930, with aviation pioneer Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown, half of the famous Alcock and Brown non-stop Atlantic crossing team, presiding over the ceremony.

Heritage Status & Local Legacy

In 2003, the monument was designated as a Grade II listed structure, recognized for its intricacy and historical importance as a memorial tied to a landmark in aviation history.

Placement-wise, it stands at Stepney Road near the Memorial Square, fenced within a small garden, ensuring it's centrally visible yet respectfully enclosed.

The monument serves as a poignant reminder that history often unfolds in unexpected places and that Burry Port, for one remarkable day in 1928, became part of a story that captured the world’s imagination.

Additional Commemorations

For the 75th anniversary of Earhart’s landing in 2003, Burry Port held a special Amelia Earhart Festival. This celebration reignited community pride and remembrance of that historic moment. A restored wooden buoy, originally used to moor the "Friendship" at the estuary, was refurbished and installed near the harbour with a commemorative plaque.

The town also features the Amelia Earhart Gardens and an engraved commemorative stone, further embedding her achievement into Burry Port’s local heritage and communal memory.

Artistic tributes have also marked her legacy. Notably, aviation artist Ruth Lewis created watercolour paintings of the "Friendship", inspired by the 75th anniversary celebrations. Her work has been featured in exhibitions, further enshrining Earhart’s connection with the community.

Summary

Landing Date: 18 June 1928, on the waters of the Loughor Estuary.

First Woman to Fly the Atlantic: Commissioned after that feat.

Monument Unveiling: By Sir Arthur Whitten-Brown in August 1930.

Design: Obelisk with weathervane shaped like Friendship; commemorative plaques.

Heritage Recognition: Grade II listed in 2003.

Additional Memorials: Buoy marker and commemorative stone added in 2003.

Amelia Earhart Worldwide Links

This page will try to link contact and access details to as many Groups, Associations, Museum's, Places of interest that have a connection with Amelia Earhart. Please contact us if you would like to be listed or have a mention.

Amelia Earhart | National Air and Space Museum

The Smithsonian Institution is the world’s largest museum, education, and research complex, with 21 museums, 14 education and research centers, and the National Zoo, shaping the future by preserving heritage, discovering new knowledge, and sharing our resources with the world. The Institution was founded in 1846 with funds from the Englishman James Smithson (1765–1829) according to his wishes “under the name of the Smithsonian Institution, an establishment for the increase and diffusion of knowledge.”

We continue to honor this mission and invite you to join us in our quest.

Smithsonian Institution

Nauticos Expedition Portal

Amelia Rose Earhart is an around-the-world pilot, international keynote speaker, author, and artist. Known for her bold approach to adventure, she flew a single-engine Pilatus PC-12 around the globe in 2014 and has inspired audiences worldwide with her message of resilience and exploration. Now, Amelia is bringing her entrepreneurial energy and creative lens to the Nauticos team, helping to share the story of the next search for Amelia Earhart’s plane and rally the support needed to make it possible. With a background in journalism and a passion for connecting people to big ideas.

Amelia is eager to bring the next Nauticos search to life, turning curiosity into action, and transforming one of history’s greatest mysteries into a mission the whole world can follow.

Amelia Rose Earhart Joins the Nauticos Team

Response to Deep Sea Vision’s Sonar Target in the Search for Amelia Earhart

Nauticos has surveyed 1860nm2 across 3 expeditions in 2002, 2006, and 2017.

Combined with the Waitt Institute’s search in 2009, 3610nm2 have previously been surveyed without locating the aircraft. This is an area close to the size of Connecticut. The sonar target DSV has detected, appears to be consistent with the sonar signature of an airplane, however, long range sonar images have historically proven to be deceiving, especially in areas with geological formations.

Yes, the sonar target appears to have a fuselage, wings, and a tail, but…it appears to have swept wings, the relative dimensions do not match the Electra, and there is a lack of engine nacelles. Those characteristics are not consistent with a Lockheed Electra 10E.All airplane “like” targets in the vicinity of Howland Island have the potential to be Amelia’s Electra and should be positively identified.

All credible fuel endurance studies indicate she ran out of fuel around the time of her last transmission at 08:43. One hour after she reportedly radioed “½ hour fuel remaining. ”Nauticos historic radio testing and analysis has determined that she was just outside visual range of the Coast Guard cutter Itasca positioned at Howland Island at 08:00.

Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum

House History

Amelia Earhart's maternal grandfather began construction on this wood-frame, Gothic Revival cottage in 1861. Located at 223 N. Terrace the home is perched high on the west bank of the scenic Missouri River.

Amelia was born in the home on July 24, 1897, to Edwin Stanton Earhart and Amy Otis Earhart. She lived in her maternal grandparent's house on and off through 8th grade. She considered this house to be her childhood home and Atchison to be her hometown. The Amelia Earhart Birthplace represents one of the most tangible links to Amelia Earhart.

Between 1918 and 1984 the home had three owners, each making their own impact on the house. In 1984 a local doctor, Dr. Eugene J. Bribach, donated $100,000 for the purchase and maintenance of the house to The Ninety-Nines, an International Organization of Women Pilots (to which Amelia not only belonged but also served as their inaugural president). It is this donation that created the Amelia Earhart Birthplace Museum.